Arsitektur 5G: Security dan Mobility

Sekarang kita melihat lebih dekat dua fitur unik dari jaringan seluler—dukungannya untuk keamanan dan mobilitas—keduanya membedakannya dari WiFi. Berikut ini juga berfungsi untuk mengisi beberapa detail tentang bagaimana masing-masing UE terhubung ke jaringan.

Kita mulai dengan arsitektur keamanan, yang didasarkan pada dua asumsi kepercayaan. Pertama, setiap Base Station percaya bahwa ia terhubung ke Mobile Core oleh private network yang aman, di mana ia membangun tunnel yang diperkenalkan pada Gambar 11: terowongan GTP/UDP/IP ke Core's User Plane (Core-UP) dan SCTP/IP tunnel ke Core's Control Plane (Core-CP). Kedua, setiap UE memiliki kartu SIM yang disediakan oleh operator, yang secara unik mengidentifikasi pelanggan (yaitu, nomor telepon) dan menetapkan parameter radio (misalnya, pita frekuensi) yang diperlukan untuk berkomunikasi dengan Base Station operator tersebut. Kartu SIM juga menyertakan kunci rahasia yang digunakan UE untuk mengautentikasi dirinya sendiri.

With this starting point, Figure 16 shows the per-UE connection sequence. When a UE first becomes active, it communicates with a nearby Base Station over a temporary (unauthenticated) radio link (Step 1). The Base Station forwards the request to the Core-CP over the existing tunnel, and the Core-CP (specifically, the MME in 4G and the AMF in 5G) initiates an authentication protocol with the UE (Step 2). 3GPP identifies a set of options for authentication and encryption, where the actual protocols used are an implementation choice. For example, Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is one of the options for encryption. Note that this authentication exchange is initially in the clear since the Base Station to UE link is not yet secure.

Dengan titik awal ini, Gambar 16 menunjukkan urutan koneksi per-UE. Ketika UE pertama kali menjadi aktif, UE berkomunikasi dengan Base Station terdekat melalui radio link sementara (tidak diautentikasi) (Langkah 1). Base Station meneruskan permintaan ke Core-CP melalui tunnel yang ada, dan Core-CP (khususnya, MME di 4G dan AMF di 5G) memulai protokol otentikasi dengan UE (Langkah 2). 3GPP mengidentifikasi serangkaian opsi untuk otentikasi dan enkripsi, di mana protokol aktual yang digunakan adalah pilihan implementasi. Misalnya, Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) adalah salah satu opsi untuk enkripsi. Perhatikan bahwa pertukaran autentikasi ini pada awalnya sudah jelas karena tautan Stasiun Pangkalan ke UE belum aman.

Once the UE and Core-CP are satisfied with each other’s identity, the Core-CP informs the other components of the parameters they will need to service the UE (Step 3). This includes: (a) instructing the Core-UP to initialize the user plane (e.g., assign an IP address to the UE and set the appropriate QCI parameter); (b) instructing the Base Station to establish an encrypted channel to the UE; and (c) giving the UE the symmetric key it will need to use the encrypted channel with the Base Station. The symmetric key is encrypted using the public key of the UE (so only the UE can decrypt it, using its secret key). Once complete, the UE can use the end-to-end user plane channel through the Core-UP (Step 4).

Setelah UE dan Core-CP puas dengan identitas masing-masing, Core-CP menginformasikan komponen lain tentang parameter yang mereka perlukan untuk melayani UE (Langkah 3). Ini termasuk: (a) menginstruksikan Core-UP untuk menginisialisasi bidang pengguna (misalnya, menetapkan alamat IP ke UE dan mengatur parameter QCI yang sesuai); (b) menginstruksikan Base Station untuk membuat saluran terenkripsi ke UE; dan (c) memberikan UE kunci simetris yang diperlukan untuk menggunakan saluran terenkripsi dengan Base Station. Kunci simetris dienkripsi menggunakan kunci publik UE (jadi hanya UE yang dapat mendekripsinya, menggunakan kunci rahasianya). Setelah selesai, UE dapat menggunakan saluran pesawat pengguna ujung ke ujung melalui Core-UP (Langkah 4).

There are three additional details of note about this process. First, the secure control channel between the UE and the Core-CP set up during Step 2 remains available, and is used by the Core-CP to send additional control instructions to the UE during the course of the session.

Second, the user plane channel established during Step 4 is referred to as the Default Bearer Service, but additional channels can be established between the UE and Core-UP, each with a potentially different QCI value. This might be done on an application-by-application basis, for example, under the control of the Mobile Core doing Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) on the traffic, looking for flows that require special treatment.

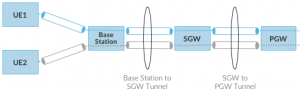

Third, while the resulting user plane channels are logically end-to-end, each is actually implemented as a sequence of per-hop tunnels, as illustrated in Figure 17. (The figure shows the SGW and PGW from the 4G Mobile Core to make the example more concrete.) This means each component on the end-to-end path terminates a downstream tunnel using one local identifier for a given UE, and initiates an upstream tunnel using a second local identifier for that UE. In practice, these per-flow tunnels are often bundled into an single inter-component tunnel, which makes it impossible to differentiate the level of service given to any particular end-to-end UE channel. This is a limitation of 4G that 5G has ambitions to correct.

Support for mobility can now be understood as the process of re-executing one or more of the steps shown in Figure 16 as the UE moves throughout the RAN. The unauthenticated link indicated by (1) allows the UE to be known to all Base Station within range. (We refer to these as potential links in later chapters.) Based on the signal’s measured CQI, the Base Stations communicate directly with each other to make a handover decision. Once made, the decision is then communicated to the Mobile Core, re-triggering the setup functions indicated by (3), which in turn re-builds the user plane tunnel between the Base Station and the SGW shown in Figure 17 (or correspondingly, between the Base Station and the UPF in 5G). One of the most unique features of the cellular network is that the Mobile Core’s user plane (e.g., UPF in 5G) buffers data during the handover transition, avoiding dropped packets and subsequent end-to-end retransmissions.

In other words, the cellular network maintains the UE session in the face of mobility (corresponding to the control and data channels depicted by (2) and (4) in Figure 16, respectively), but it is able to do so only when the same Mobile Core serves the UE (i.e., only the Base Station changes). This would typically be the case for a UE moving within a metropolitan area. Moving between metro areas—and hence, between Mobile Cores—is indistinguishable from power cycling a UE. The UE is assigned a new IP address and no attempt is made to buffer and subsequently deliver in-flight data. Independent of mobility, but relevant to this discussion, any UE that becomes inactive for a period of time also loses its session, with a new session established and a new IP address assigned when the UE becomes active again.

Note that this session-based approach can be traced to the cellular network’s roots as a connection-oriented network. An interesting thought experiment is whether the Mobile Core will continue to evolve so as to better match the connectionless assumptions of the Internet protocols that typically run on top of it.